MATLAB Examples 1 (covering Statistics Lectures 1 and 2)

Contents

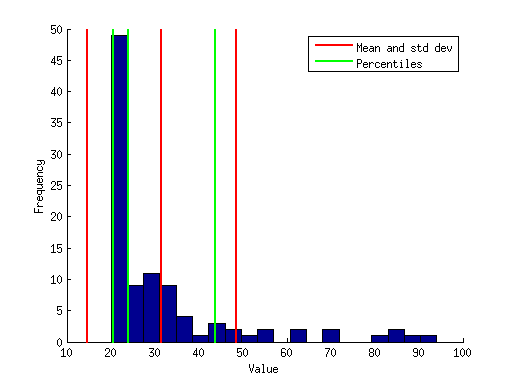

Example 1: Simple data plotting

% generate some fake data x = (randn(1,100).^2)*10 + 20; % compute some simple data summary metrics mn = mean(x); % compute mean sd = std(x); % compute standard deviation ptiles = prctile(x,[16 50 84]); % compute percentiles (median and central 68%) % make a figure figure; hold on; hist(x,20); % plot a histogram using twenty bins ax = axis; % get the current axis bounds % plot lines showing mean and +/- 1 std dev h1 = plot([mn mn], ax(3:4),'r-','LineWidth',2); h2 = plot([mn-sd mn-sd],ax(3:4),'r-','LineWidth',2); h3 = plot([mn+sd mn+sd],ax(3:4),'r-','LineWidth',2); % plot lines showing percentiles h4 = []; for p=1:length(ptiles) h4(p) = plot(repmat(ptiles(p),[1 2]),ax(3:4),'g-','LineWidth',2); end legend([h1 h4(1)],{'Mean and std dev' 'Percentiles'}); xlabel('Value'); ylabel('Frequency');

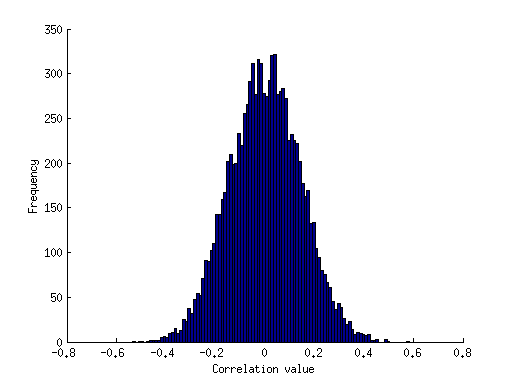

Example 2: Monte Carlo simulations of correlation values

% define numsim = 10000; % number of simulations to run samplesize = 50; % number of data points in each sample % pre-allocate the results vector results = zeros(1,numsim); % loop over simulations for num=1:numsim % draw two sets of random numbers, each from the normal distribution data = randn(samplesize,2); % compute the correlation between the two sets of numbers and store the result results(num) = corr(data(:,1),data(:,2)); end % visualize the results figure; hold on; hist(results,100); ax = axis; mx = max(abs(ax(1:2))); % make the x-axis symmetric around 0 axis([-mx mx ax(3:4)]); xlabel('Correlation value'); ylabel('Frequency');

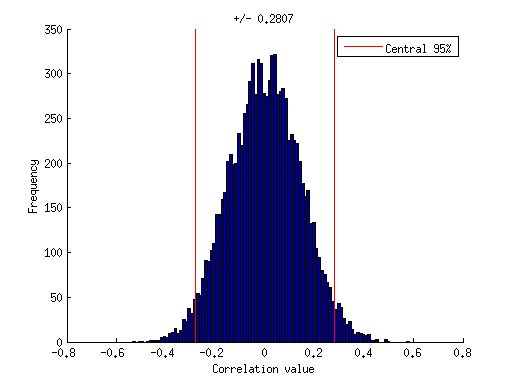

% although the two sets of numbers were drawn from independent % probability distributions (and so should on average exhibit % zero correlation), due to our limited sample size, we sometimes % observe positive or negative correlation values. what is the % value below which most correlation magnitudes lie? let's use % 95% as the definition of "most". val = prctile(abs(results),95); val

val =

0.280698330593468

% visualize this on the figure ax = axis; h1 = plot([val val],ax(3:4),'r-'); h2 = plot(-[val val],ax(3:4),'r-'); legend(h1,'Central 95%'); title(sprintf('+/- %.4f',val));

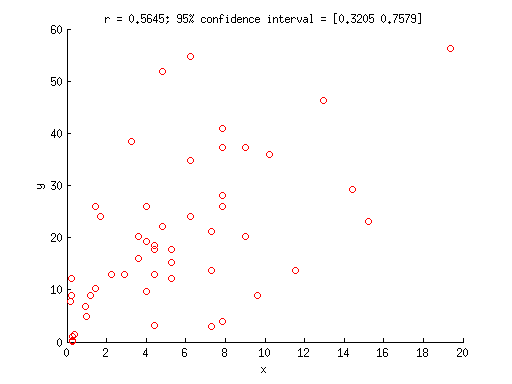

Example 3: Use bootstrapping to obtain confidence intervals on a correlation

% generate some fake data x = [2.5 2.8 3.4 2 1.2 2.1 1.8 2.8 1.1 2.2 3.2 0.61 3 0.53 2 0.45 2 ... 1 -0.53 1.2 2.2 2.5 1.9 1.9 2.8 2.8 1.3 3.1 2.7 2.3 0.47 2.1 1.5 3.8 ... 3 2.8 0.97 2.5 2.3 3.9 0.54 3.6 2.3 2.7 4.4 2.7 0.44 2.1 1.7 2.1].^2; y = [5.9 6.4 3.7 3.1 5.1 3.6 6.2 5.1 3 4.7 6 1.2 6.1 -0.51 4.4 3 ... 5.1 2.2 0.14 3.2 7.2 7.4 4 4.5 5.3 2 4.9 3 4.6 3.9 3.5 4.2 3.6 5.4 ... 4.5 6.1 2.6 4.9 3.5 4.8 1 6.8 4.2 3.7 7.5 1.7 2.8 1.8 3.6 4.3].^2; % compute the actual correlation value observed actualcorr = corr(x(:),y(:)); % draw bootstrap samples and compute correlation values results = zeros(1,10000); for num=1:10000 % vector of indices (each element is a random integer between % 1 and n where n is the number of data points) ix = ceil(length(x) * rand(1,length(x))); % compute correlation using those data points results(num) = corr(x(ix)',y(ix)'); end % alternatively, you could use MATLAB's bootstrp.m function to achieve the same result: % results = bootstrp(10000,@(x0,y0) corr(x0,y0),x',y'); % what is the central 95% of the bootstrap results? ptiles = prctile(results,[2.5 97.5]); % visualize figure; hold on; scatter(x,y,'ro'); xlabel('x'); ylabel('y'); title(sprintf('r = %.4f; 95%% confidence interval = [%.4f %.4f]',actualcorr,ptiles(1),ptiles(2)));

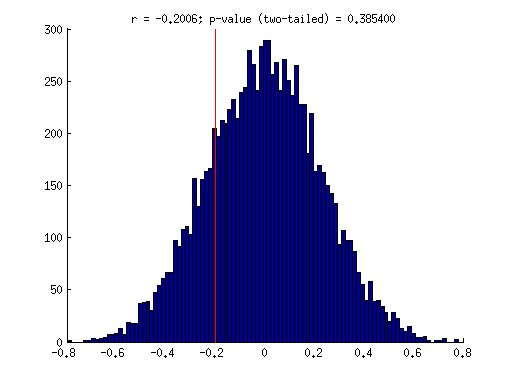

Example 4: Use randomization to assess the statistical significance of a correlation

% generate some fake data x = [0.84 0.29 0.84 0.85 0.021 0.52 1 0.64 0.27 0.55 0.078 0.26 0.78 0.67 0.37 0.22 0.62 0.39 0.71 0.24]; y = [0.52 0.38 0.21 0.27 0.83 0.65 0.64 0.26 0.34 0.55 0.87 0.21 0.22 0.84 0.42 0.23 0.68 0.68 0.64 0.61]; % compute the actual correlation value observed actualcorr = corr(x(:),y(:)); % we pose the null hypothesis that there is no dependency between the % x-values and the y-values. thus, under the null hypothesis, we should % be able to break the association between x and y. % perform randomization results = zeros(1,10000); for num=1:10000 % vector of indices (a random ordering of the integers between % 1 and n where n is the number of data points) ix = randperm(length(x)); % compute correlation between randomly shuffled x-values and the y-values results(num) = corr(x(ix)',y'); end % visualize figure; hold on; hist(results,100); ax = axis; plot(repmat(actualcorr,[1 2]),ax(3:4),'r-'); % compute the p-value as the fraction of the distribution that % is more extreme than the actually observed correlation value. % we use absolute value so that both positive and negative correlations % count as "extreme". this is referred to as a two-tailed test. pval = sum(abs(results) > abs(actualcorr)) / length(results); title(sprintf('r = %.4f; p-value (two-tailed) = %.6f',actualcorr,pval));

% the actual correlation value (-0.2) is fairly weak. under the null % hypothesis, we would expect to find correlation values of that size % or larger about 40% of the time. thus, we do not have sufficient % evidence to reject the null hypothesis. in other words, the % actual correlation value observed is deemed not statistically % significant.